Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What is the

cProfilemodule and what is it used for?What type of information does

cProfileprovide?Objectives

Learn how to use

cProfileto obtain information about bottlenecks in your program.Learn about function profiling.

Experiment with using

cProfileto analyze a program.

Python provides a C module called cProfile, and using it is quite simple. All you need to do is import the module and call its run function.

import cProfile

import re

cProfile.run('re.compile("foo|bar")')

The output from cProfile looks like this:

185 function calls (180 primitive calls) in 0.000 seconds

Ordered by: standard name

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 <string>:1(<module>)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 re.py:222(compile)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 re.py:278(_compile)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:221(_compile_charset)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:248(_optimize_charset)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:412(_compile_info)

2 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:513(isstring)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:516(_code)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:531(compile)

3/1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_compile.py:64(_compile)

3 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:105(__init__)

5 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:153(__len__)

12 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:157(__getitem__)

7 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:165(append)

3/1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:167(getwidth)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:217(__init__)

8 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:226(__next)

2 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:242(match)

6 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:247(get)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:276(tell)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:429(_parse_sub)

2 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:491(_parse)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:70(__init__)

2 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:75(groups)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:797(fix_flags)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 sre_parse.py:819(parse)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method _sre.compile}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.exec}

17 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.isinstance}

25/24 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.len}

2 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.max}

9 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.min}

6 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.ord}

48 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'append' of 'list' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'disable' of '_lsprof.Profiler' objects}

5 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'find' of 'bytearray' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'items' of 'dict' objects}

The first line indicates the number of calls that were monitored. Of those calls, some were primitive, meaning that the call was not induced via recursion. The next line, “Ordered by: standard name”, indicates that the text string in the last column was used to sort the output. The column headings (from left to right) are:

ncalls- for the number of callstottime- for the total time spent in the given function (and excluding time made in calls to sub-functions)percall- is the quotient of tottime divided by ncallscumtime- is the cumulative time spent in this and all subfunctions (from invocation till exit). This figure is accurate even for recursive functionspercall- is the quotient of cumtime divided by primitive callsfilename:lineno(function)- provides the respective data of each function

When there are two numbers in the first column (for example 3/1), it means that the function recursed. The second value is the number of primitive calls and the former is the total number of calls. Note that when the function does not recurse, these two values are the same, and only the single figure is printed.

From IPython, the same result can be achieved by using the %prun magic command or %%prun cell magic command.

import re

%prun re.compile("foo|bar")

It’s also possible to run a program under the cProfile module from the command line:

python -m cProfile [-o output_file] [-s sort_order] filename.py

Using cProfile

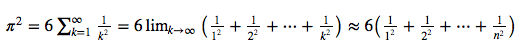

As an example, suppose we would like to evaluate the summation of the reciprocals of squares up to a certain integer n for evaluating π. The relation we want to use has been proven by Euler in 1735 and is known as the Basel problem.

A simple Python function for evaluating the truncated sum looks like this:

def recip_square(i):

return 1./i**2

def approx_pi(n=10000000):

val = 0.

for k in range(1,n+1):

val += recip_square(k)

return (6 * val)**.5

Challenge

First, start by timing how long it takes to evaluate the function using the default value of n.

Now, let’s profile the code using the %prun magic command (use the cProfile module if you’re running directly from Python):

%prun approx_pi()

This will take a few seconds to run, then you should see the following:

10000004 function calls in 6.522 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

10000000 4.433 0.000 4.433 0.000 <ipython-input-4-8fdaa89ffea3>:1(recip_square)

1 2.089 2.089 6.522 6.522 <ipython-input-4-8fdaa89ffea3>:4(approx_pi)

1 0.000 0.000 6.522 6.522 {built-in method builtins.exec}

1 0.000 0.000 6.522 6.522 <string>:1(<module>)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'disable' of '_lsprof.Profiler' objects}

The first line of the profile contains the number of CPU seconds it took to run the code. You should see that the code was slower overall

than the first run. This was because it ran inside the cProfile module.

Looking at the tottime column, we can see that approximately one third of the time is spent in approx_pi and the remainder

is spent in recip_square.

In the Python Performance Tips lesson, we learnt that there is considerable overhead in a function call, so let’s try the same code without the extra function. Here’s the source code:

def approx_pi2(n=10000000):

val = 0.

for k in range(1,n+1):

val += 1./k**2

return (6 * val)**.5

Now, let’s profile this code using the %prun magic command again:

%prun approx_pi2()

Here is the output:

4 function calls in 3.979 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

1 3.979 3.979 3.979 3.979 <ipython-input-7-182438f93e7d>:1(approx_pi2)

1 0.000 0.000 3.979 3.979 {built-in method builtins.exec}

1 0.000 0.000 3.979 3.979 <string>:1(<module>)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'disable' of '_lsprof.Profiler' objects}

Wow, that made a big difference! However, examining the output from this command, you should see that a significant portion of time is still being spent in one function.

Challenge

Using your knowledge from the course so far, modify the code to reduce or eliminate this overhead. Time how long your new version takes to execute, and calculate the speedup using the equation speedup = original_time / optimized_time. For example, if the original time was 2.1 seconds and the optimized time was 340ms, then the speedup would be 2210 / 340 = 6.5 times. Note that both the values need to use the same units (seconds, milliseconds, microsectonds, etc.)

Key Points

cProfileprovides information about the functions in a program.There is some overhead when using

cProfileto analyze a program.